Mental Capacity Act

Introduction

This Policy aims to support Dan Devitt Consultancy Services Ltd. contractual environments where people are involved in the care and/or treatment of a person who is over 16, and may lack capacity in relation to specific decisions at the time that they need to be made. This policy provides a guide to the assessment of the decision-making capacity of the people DDCS contractual environments may encounter.

DDCS staff currently do not regularly make assessments of the mental capacity of the people they care for, to make decisions, as part of their day-to-day work. Despite this, and to ensure that DDCS can fully fulfil a broad range of contractual arrangements, this policy has been drafted in the case of a delivery context that necessitates the delivery of Mental Capacity Act elements (specifically assessments of capacity) with regards to consenting to or refusing consent for health-related procedures.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 sets out a statutory basis for the assessment of mental capacity, and defines assessment responsibilities for a potentially broad range of Health and Social Care professionals.

The Assessor could be any person of those involved in the care of a person who may lack capacity.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a statutory framework in England and Wales, for supporting people aged 16 and over to make their own decisions, alongside setting out the legal framework for people who lack capacity to make decisions for themselves, or who have capacity and want to prepare for a time when they may lack capacity in the future. It sets out who can take decisions, in which situations, and how they should go about this. The Act came into force in 2007 and has been updated through the Mental Capacity Amendment Act 2019.

The Act’s legal framework is supported by the Code of Practice, which provides guidance and information about how the Act works in practice. The Act and Code are important parts of the UK’s commitment to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006, regarding promoting and protecting the rights and freedoms of people who may lack capacity to make decisions.

The Code of Practice, 2013 has statutory force, which means that certain categories of people have a legal duty to have regard to it when working with or caring for adults who may lack capacity to make decisions for themselves.

The Code of Practice provides guidance to anyone who is working with or caring for people who may lack capacity to make decisions. It describes how they should try to support people to make their own decision as far as possible, and their responsibilities when acting or making decisions on behalf of individuals if they lack the capacity to act or make these decisions for themselves.

The Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019 has changed the process for authorising arrangements enabling the care and treatment of people who lack capacity to consent to the arrangements which give rise to a deprivation of their liberty. The Code of Practice that accompanies the amendment act is still going through the Government consultation process and this Policy will need to be updated once the new code is published.

-

Dan Devitt Consultancy Services does not currently or foreseeably have any direct contracted or subcontracted relationship or operate on its own either a registered care home or a facility or, any site that might count as a hospital site with bed spaces, or clinical setting where MCA relevant activities (assessments, decisions and implementation of MCA arrangements) are conducted.

That limitation on the scope of activities delivered by DDCS notwithstanding, this policy has been drafted to ensure that DDCS is well placed to ensure that it is delivering a fully comprehensive approach to Safeguarding and related policies and able to adapt to future changes in commissioned activities.

It stands as a visible sign of DDCS’ awareness of and commitment to the provision of safeguarding and related assurance for services that are delivered through DDCS via subcontracted entities and with a view to ensuring compliance is built into the DDCS policy framework before rather than after it becomes necessary.

Our work varies in scope across counties and local NHS Trusts, creating relationships between DDCS and Local authorities, NHS, public health providers, and other relevant organisations.

These organisations do not currently perform functions where MCA functions are entailed, but this is a situation that could potentially change over time.

To provide assurance of DDCS’ robust and forward-thinking approach to safeguarding this policy and others on different safeguarding themes have been drafted in preparation in case any of the functions do, one day, become an element of DDCS business.

DDCS will ensure that it monitors and provides assurance to its commissioners that its relationships – either to commissioning bodies or subcontracted entities - align with its commitment and obligations and accountability to commissioners for safeguarding practice and policies in subcontractors.

This will be reviewed on a regular and ongoing basis and especially at the commencement of new contractual relationships where an assessment to ensure a full compliance with relevant safeguarding practice and policies is conducted.

DDCS will evolve its safeguarding response in line with future requirements whilst constantly assessing, reflecting upon and improving its safeguarding approach and policy suite.

-

The 1948 European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) sets out a series of articles that guarantee rights to everyone and explicitly with Article 1 the universal Obligation to respect Human Rights.

This sets the tone for the other articles that together express the obligation of nation state and individual rights to protection that supports the inherent dignity of all human beings whatever their context, status, age, health status frailty or challenges.

Article 5 of the ECHR enshrines all human beings have the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be deprived of their liberty, save where this is accordance with due process under the relevant national legal framework.

As of yet, the legal ramifications of recent policy decisions by the UK Government to set aside the EHCR and replace it with domestic legislative responses are unclear, and the UKs continued adherence to the EHCR is to be confirmed, as is the precise relationship of DoLS to such any replacement overarching framework based upon human rights.

Similarly unclear is the move towards implementation of the Liberty Protection Safeguards - replacing the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS).

The UKs continued adherence to the EHCR is to be confirmed, as is the precise relationship of any replacement overarching framework based upon human rights, or any timetable for the proposed implementation of the Liberty Protection Standards in place of the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards.

The Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019 replaces DoLS with the with Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS).

On 5 April 2023 the Department of Health and Social Care announced the implementation of the Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS), the Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019, will be delayed “beyond the life of this Parliament”. The current government did a press release on 18 October 2025 about their plan to launch a consultation on LPS in 2026, suggesting that it is unlikely to be introduced any time before mid to late 2026.

The Liberty Protection Safeguards have been designed to put the rights and wishes of those people at the centre of all decision making on deprivation of liberty.

The amendment will provide protection for people aged 16 and above who need to be deprived of their liberty in order to enable their care or treatment, and who lack the mental capacity to consent to their arrangements. There are likely to be additional provisions for the use of the LPS framework in community settings. Even, potentially a person’s home, rather than a registered care home or similar community facility. There is currently (November 2025) no detail on the scope or limitations of any such provision outside of the outline published in 2021 and reproduced below in Appendix A.

It is proposed that there will be a one-year period of overlap between DoLS and LPS where DoLS already authorised will run until their expiry date and all DoLS under reviews and new submissions will be authorised under LPS.

The next stage of implementation will be a public consultation on the Revised MCA Code of Conduct and LPS Practice Guidance.

This Policy will be reviewed once the Government have completed the public consultation and given a firm date for implementation. It should be noted that there is cross-party agreement and commitment in support of the introduction of LPS, so it is a matter of when, but not if it is introduced.

DDCS will respond to changes in legislation and modify this Policy accordingly once the Government have completed the public consultation on the Practice Guidance for Liberty Protection Safeguards and given a firm date for implementation.

-

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 and its amendments (2019) intend to enable and support people aged 16 and over who may lack capacity, to maximise their ability to make decisions. It aims to protect the rights and interests of people who lack capacity to make particular decisions, and enable them to participate in decision-making, as far as they can do so.

Under the age of 16, capacity is usually balanced between parent, carer and the individual in question depending on the outcome of Fraser Competency or Bichard Checklist assessment. Under the age of 13, no legal consent is possible, and it is necessary to ensure parent or carer views on competency and consent are normally accommodated unless other concerns or issues impacting on decisions are present (See Safeguarding Vulnerable Children Policy November 2025 and section 16 below).

The Act states that ‘A person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material time a person is unable to make a decision for him/herself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain.’

A Mental Capacity Assessment must be decision and time-specific. A blanket statement with regards to a patient’s capacity or lack of capacity is not lawful.

The five statutory principles of the Legislation are laid out in Section 1 of the Mental Capacity Act (2005).

Assumption of capacity: “a person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity”

Assisted decision-making: “a person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them to do so have been taken without success”

Unwise decisions: “a person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because they make an unwise decision”

Best interests: “An act done or decision made under this Act for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made, in their best interests”

Less restrictive alternative: “before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the person’s rights and freedom of action”

The statutory principles of the Act aim to:

■ Empower people and encourage them to make their own decisions where possible, with support if needed

■ Help people to take part, as much as practicable, in a decision that affects them and

■ Protect the rights and interests of people who lack capacity.

The principles aim to assist and support people who may lack capacity to make a particular decision, and not to restrict or control their lives. They aim to empower people and encourage supported decision-making as well as ensuring that decisions made about a person accord as much as possible, within the law, with that person’s wishes, values, beliefs and feelings.

In some situations, decisions cannot be delayed while a person gets support to make a decision. This can happen in emergency vital act situations or when an urgent decision is required (for example, immediate medical treatment). In these situations, the only practicable and appropriate steps might be to keep a person informed of what is happening and why.

Decisions must be clearly recorded in the records.

-

The DDCS Director and wider staff have key roles and responsibilities to ensure the Organisation meets requirements set out by Statutory and Regulatory Authorities such as the Department of Health & Social Care, Commissioners and the Care Quality Commission.

The Director has overall responsibility to have processes in place to: delegate through the Safeguarding Lead to ensure that DDCS personnel and subcontracted staff are aware of this policy and adhere to its requirements and that appropriate resources exist to meet the requirements of this Policy.

The Director is responsible for ensuring that all staff responsible for operational delivery through DDCS-contracted activity are aware of this policy, understand its requirements and support its implementation.

The Safeguarding Lead is responsible for implementing the policy and ensuring that relevant assessment tools are readily available to allow DDCS personnel to carry out the duties prescribed in this policy.

All DDCS personnel have responsibility to comply with the requirements of this and associated policies and have a legal duty to adhere to the Mental Capacity Act and Code of Practice when working with, or caring for, adults who may lack capacity to make decisions for themselves.

The Safeguarding Lead is responsible for reviewing and monitoring practice and offering support and training to enhance DDCS’ knowledge and skills when assessing capacity. They will also quality-assure any or all completed Mental Capacity Act Assessments and take appropriate action to support staff in improving practice.

Currently, DDCS does not have any operational or staffing element requiring direct MCA delivery. If this position alters considering changed context, contracted activities, or issues, all staff who assess, treat, or care for patients and require consent to do so, will need to be able to complete MCA assessments and within Dan Devitt Consultancy Services Ltd. be mandated to attend MCA training with updates every 3 years.

-

The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) does not lay down professional roles or require certain qualifications to undertake capacity assessments.

The MCA is very clear that the individual who is going to take action or make a decision on behalf of an adult should be the person who assesses their capacity. The decision maker or assessor has to ‘satisfy themselves’ that the relevant person lacks capacity in the matter to be decided if they intend to make a “best interest’s” decision.

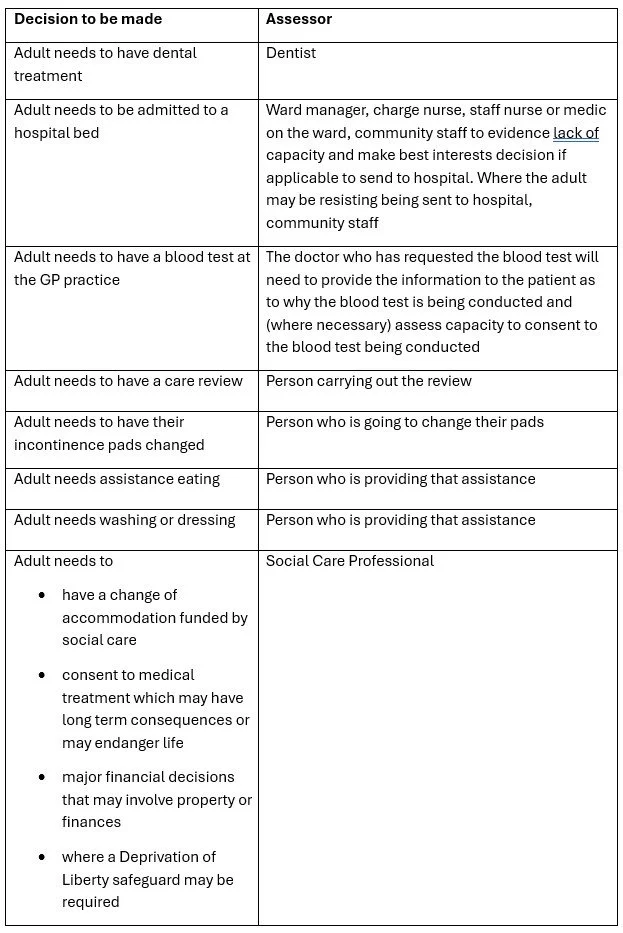

See Table 1 below - This is not exhaustive & professional judgement must be used. An MCA Assessment Form must be used to complete this assessment. All completed MCA Assessment Forms must be stored in the Service users Electronic and paper record and a copy or task sent to the Safeguarding Lead for review and quality assurance via daniel.devitt@ddconsultancyservices.com

You can find the East London NHS Foundation Trust MCA Assessment Form here as an example, though different local NHS Trusts and Local Authorities (Councils and their MCA providers) have varying MCA Assessment Forms and contacts.

Consideration should be given as to whether there should be a second assessor present at the assessment for some cases. This may be where there is known conflict about care and support, where there may be a dispute with the family, where capacity is fluctuating or where there is the need for significant restraint. For some complex cases a multidisciplinary team may need to be involved, or it may be necessary to obtain the opinion of a psychiatrist.

In line with MCA (2005) the DDCS MCA policy does not allow permissive decisions to be made in the best interests of a person lacking capacity in relation to the following:

■ Consenting to marriage or civil partnership

■ Consenting to have sexual relations

■ Consenting to divorce or dissolution of civil partnerships

■ Consenting to placement of a child for adoption or making of an adoption order

■ Discharge of parental responsibility in matters not relating to a child’s property

■ Consenting under the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act

■ Voting in any election or referendum

■ Writing a Will

Any approaches to DDCS personnel with regards to situations involving these prohibited circumstances must be reported to the Safeguarding Lead.

-

There are occasions when adults may refuse to engage in assessment of their capacity to make a specific decision. All efforts should be made to establish a rapport with the person and seek their engagement, and to explain the consequences of not making the relevant decision (MCA Code of Practice 2013).

Where an individual refuses to engage because they do not understand (due to their impairment or disturbance of the mind or brain whether temporary or permanent), then the decision maker can conclude, on the balance of probabilities, that the individual lacks capacity to agree or refuse the assessment and the assessment can normally go ahead, although no one can be forced to undergo an assessment of capacity (MCA & DoLS, 2018).

-

All practicable steps must be taken to help someone to make their own decisions before it can be concluded that they lack capacity to make that decision themselves. The Act underlines, these steps (such as helping individuals to communicate) must be taken in a way which reflects the person’s individual circumstances and meets their particular needs.

The Act applies to a wide range of people with different conditions that may affect their capacity to make particular decisions. Therefore, the appropriate steps required will depend on:

■ a person’s individual circumstances (for example, somebody with learning difficulties may need a different approach to somebody with dementia)

■ the decision the person has to make, and

■ the length of time they have to make it.

The purpose of support is to enable the person to make their own decision. The person giving support may think a specific decision is best. But they should not pressure the person they are supporting into choosing that specific decision. This is particularly important where the person’s life experiences mean that they have only very limited experience of being allowed to make their own decisions.

Providing appropriate support with decision-making should be a core part of a person-centred approach to the care and support planning process.

It is important to provide information that will help the person to make decisions and to tailor that information to the individual’s needs and abilities. Information must also be in the easiest and most appropriate form of communication for the person concerned.

For example, some people respond better when given information verbally, others may like to read a leaflet before they decide. Some may also require support from a carer or friend who may know how best to communicate with the person, or their preferred way to receive information.

Any person helping someone to make a decision for themselves should follow these steps:

■ Take time to explain anything that might help the person make a decision. It is important that they have access to all the information they need to make an informed decision, including the nature of the decision and why it needs to be made.

■ Try not to give more detail than the person needs as this might confuse them. In some cases, a simple, broad explanation will be enough. But it must not miss out important relevant information.

■ What are the risks and benefits? Describe any foreseeable consequences of making the decision, and of not making any decision now or at all.

■ Explain the effects the decision might have on the person and those close to them – including anyone involved in their care.

■ If they have a choice, give them the information for each of the options, in a balanced way.

■ For some types of decisions, it may be important to give access to advice from elsewhere. This may be independent or specialist advice (for example, from a medical practitioner or a financial or legal adviser). But it might simply be advice from trusted friends or relatives.

Persons involved in this must make a record of the information provided and the steps taken to communicate it.

To help someone decide for themselves, all possible and appropriate means of communication should be tried:

■ Explain the effects the decision might have on the person and those close to them – including anyone involved in their care.

■ If they have a choice, give them the information for each of the options, in a balanced way.

■ For some types of decisions, it may be important to give access to advice from elsewhere. This may be independent or specialist advice (for example, from a medical practitioner or a financial or legal adviser). But it might simply be advice from trusted friends or relatives.

■ It may be helpful to make a record of the information provided and the steps taken to communicate it.

To help someone decide for themselves, all possible and appropriate means of communication should be tried:

■ The first step should be to ask the person if they would like any help, or if there is anyone who they would like to be there with them, for example, relatives, friends, a GP, social worker, religious community member, any attorneys appointed under a Lasting Power of Attorney, or deputies appointed by the Court of Protection.

■ Ask people who know the person well about the best form of communication (try speaking to family members, carers, day centre staff or support workers). They may also know somebody the person can communicate with easily, or the time when it is best to communicate with them.

■ Use appropriate language. Where appropriate, use pictures, objects or illustrations to demonstrate ideas.

■ Speak at the right volume and speed, with appropriate words and sentence structure. It may be helpful to pause to check understanding, to ask open questions that check understanding, or show that a choice is available.

■ Break down difficult information into smaller points that are easy to understand. Allow the person time to consider and understand each point before continuing.

■ It may be necessary to repeat information or go back over a point several times, to enable the individual to retain the information long enough to make an effective decision.

Other contextual and inherent factor to consider:

■ Be aware of cultural, ethnic or religious factors that may influence a person’s way of thinking, behaviour or communication. For example, some people may be used to involving members of their community in decision-making. Someone’s religious beliefs may influence their approach to medical treatment decisions. Awareness of cultural considerations should be balanced with awareness of other relevant considerations such as undue pressure or coercion, and safeguarding duties.

■ For people with specific communication or cognitive problems, firstly find out how they are used to communicating; it may be appropriate to seek advice or support from a speech and language therapist. Do they use a picture board, Makaton, or assistive technology? Are they hearing or visually impaired and need their hearing aids or an interpreter or sign language practitioner? For people who use non-verbal methods of communication, their behaviour (in particular, changes in behaviour or distress) can provide indications of their feelings.

■ Careful consideration should also be given to both the location and timing of the assessment. Where possible, the location should be somewhere where the person feels most at ease, somewhere quiet, where there are minimal interruptions and where their privacy and dignity can be respected and where they are free from undue influence to make their own decision.

■ Try to choose a time of day when they are most receptive and allow them time to consider or ask for clarification. If possible, delay the decision if to enable further steps to be taken to assist people to make their own decision.

■ Having someone that they know to support people during the decision-making process may help to put them at their ease and reduce anxiety. They make be able to suggest who they would like to help them and who would not be helpful to them.

It is important to make sure that the person is happy to receive support and that they trust the person who is supporting them. All practicable steps should be taken to avoid the risk of coercion or undue influence.

If there are no significant trusted people, or no-one willing to provide support, then it may be appropriate to consider an Advocate.

-

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 works on the principle that everyone has a right to make their own decisions and that we presume that people have the capacity to make their own decisions unless there is a proper reason to doubt this. The MCA only applies to people who have an impairment in cognitive functioning either on a temporary or permanent basis. There does not need to be a formal diagnosis but can be based on the clinical presentation, observed behaviour, records, information from others or in the professional opinion based on the interview with the service user.

If there is no impairment or disturbance in the mind or brain, then the person does not lack capacity within the meaning of the MCA, and the assessment cannot proceed.

All attempts should be made to assist service users to make their own decisions. Information should be given in an appropriate format that is accessible for their particular needs. If necessary consideration should be given to delaying the assessment if it is possible so that specialist assistance can be given to enable the Service user to make their own decision.

When considering a person’s capacity to make a specific decision, it is important to consider:

■ Does the person have all the relevant information they need to make the decision?

■ If they are making a decision that involves choosing between alternatives, do they have information on all the different options?

■ Would the person have a better understanding if information was explained or presented in another way?

■ Are there times of day when the person’s understanding is better?

■ Are there locations where they may feel more at ease?

■ Can the decision be put off until the circumstances are different and the person concerned may be able to make the decision?

■ Can anyone else help the person to make choices or express a view (for example, a family member or carer, an advocate or someone to help with communication)?

‘For the purposes of this Act, a person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material time he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain’.

This can be broken down into three questions:

Is the person able to make the decision (with support if required)?

If they cannot, is there an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain?

Is the person’s inability to make the decision because of the impairment or disturbance?

Question 1 – Is the person able to make the decision (with support if required)?

Can the service user:

■ Understand the nature of the decision, the purpose for which it is needed and the consequences, risks or outcomes of making the decision. The Act states every effort should be made to provide information in a way that is most appropriate to help the person understand. In determining risks the person only needs to consider the reasonably foreseeable risks. It is acceptable for the information to be understood in broad terms.

■ Retain the information for long enough to make the decision, the information could be forgotten an hour later and the decision would remain valid.

■ Weigh or use the information, taking into account any risks and consequences when making their decision.

■ Communicate their decision using any method recognised by those undertaking the assessment i.e. hand signals, gestures, writing etc.

Impairment in executive function

A common area of difficulty is where a person with an impairment of, or disturbance in, the functioning of the person’s mind or brain gives coherent answers to questions, but it is clear from their actions that they are unable to carry out their decision. This is sometimes called an impairment in their executive function. If the person cannot understand (and/or use and weigh) the fact that there is a mismatch between what they say and what they do when required to act, it can be said that they lack capacity to make the decision in question.

This could include people with eating disorders or substance misuse where their compulsion to eat or drink may be too strong to ignore. And result in them making impulsive decisions regardless of information they have been given or their understanding of it, which may indicate that they are not able to use or weigh the information (MCA Draft Code of Practice, 2022).

Question 2 - Is there an impairment of, or disturbance in, the functioning of the person’s mind or brain?

Examples of conditions:

■ Dementia

■ Significant learning disabilities

■ Long-term effects of brain damage

■ Physical or medical conditions that cause confusion, drowsiness or loss of consciousness

■ Delirium

■ Some forms of mental illness

■ Concussion following a head injury, and

■ Symptoms of alcohol or drug use.

Question 3 - Does the impairment, or disturbance in, the functioning of the person’s mind or brain prevent them from making a decision?

It is easier to establish that a person has an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain if they have a formal diagnosis of a particular condition. However, a formal diagnosis is not necessary for the purposes of the Act. It is also not necessary for the impairment or disturbance to fit into a recognised clinical diagnosis.

It is necessary to ask whether the inability of the person to make the decision is because of the impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain. This will mean explaining (for instance) how a person’s dementia means that they cannot use and weigh the information relevant to the decision in question.

So long as the impairment or disturbance can be demonstrated to be a cause of the person’s inability to make the decision, then they will lack capacity for purposes of the Act.

If the patient is unable to do any one of the 4 parts of the first question, then they lack capacity to make the decision as long as this inability can be linked to an impairment of, or disturbance in, the functioning of the person’s mind or brain, that prevents them making this decision.

If there is no impairment that prevents them making their own decision, then they are deemed to have capacity to make their own decision even if it would be considered an unwise decision (MCA Draft Code of Practice, 2022).

Fluctuating capacity

It is important to recognise that an assessment that a person lacks capacity to make a particular decision at a particular time does not mean that they always lack capacity for all decisions.

Some people may have an illness or condition, which at times, affects their decision-making ability. If a person has fluctuating or temporary loss of capacity, where possible, the decision should be delayed until the person has recovered and regained their capacity. Attempts to discuss care and treatment where consent is required should be made when the person is in their best condition and has capacity, depending on the urgency and whether this is a one off or ongoing decision.

Referral to the Court of Protection may need to be made for consideration when a person has fluctuating capacity and make a judgement for ongoing decisions.

If you think this is required, please speak to the DDCS Safeguarding Lead.

Reviewing Capacity assessments

Capacity assessments should be reviewed from time to time, as decision making capabilities may improve with time and rehabilitation. Capacity should be reviewed whenever new decisions need to be made and when care plans are reviewed and updated. For day-to-day decisions some people may have capacity to make some decisions but not others and capacity may fluctuate over time. Care plans need to reflect capacity for specific decisions.

Having decided on and documented that the person lacks capacity to make the specific decision, ascertain if there is an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment, Lasting Power of Attorney or Court Appointed Deputy. If any of these are present guidance should be sought from them.

-

It is a general principle of law and professional practice that people have a right to consent to or refuse treatment. The courts have recognised that adults have the right to say in advance that they want to refuse treatment if they lose capacity in the future – even if this results in their death. A valid and applicable advance decision to refuse treatment has the same force as a contemporaneous decision.

To make an advanced decision to refuse treatment a person must be 18 years of age or older and have the capacity to make the decision. A young person (under the age of 18) cannot make an advance decision, however they can make an advance (written) statement setting out their preferences, which any decision-maker should consider.

Healthcare professionals must follow an advance decision if it is valid and applies to the particular circumstances. If they do not, they could face criminal prosecution or civil liability.

Advance decisions can have serious consequences for the people who make them. They can also have an important impact on family and friends, and professionals involved in their care. Before healthcare professionals can apply an advance decision, there must be proof that the decision:

■ exists

■ is valid, and

■ is applicable in the current circumstances.

An advance decision to refuse treatment:

■ must state precisely what treatment is to be refused – a statement giving a general desire not to be treated is not enough.

■ may set out the circumstances when the refusal should apply – it is helpful to include as much detail as possible.

■ will only apply at a time when the person lacks capacity to consent to or refuse the specific treatment.

■ should include a statement of values, for example an individual might want to state whether it is more important to them that they be kept pain free rather than kept alive.

For most people, there will be no doubt about their capacity to make an advance decision. Even those who lack capacity to make some decisions may have the capacity to make an advance decision. It may be helpful to get evidence of a person’s capacity to make the advance decision (for example, if there is a possibility that the advance decision may be challenged in the future). It is also important to remember that capacity can change over time, and a person who lacks capacity to make a decision now might be able to make it in the future (MCA Draft Code of Practice, 2022).

It is essential that where an advance directive is made, a copy of this is held in the individual’s clinical records and that the individual is encouraged to share copies with family and those health and social care professionals coordinating their care.

An advance directive must be followed where it is concluded that an individual lacks capacity to make a specific decision about their medical treatment and it is known that they have previously made a valid and applicable advance directive (relating to the proposed specific medical treatment). If it is a refusal of life sustaining treatment then it must contain a statement that the advance decision applies even if your life is at risk. Decision makers are advised to consult senior clinicians as required.

A written document can be evidence of an advance decision. It is helpful to tell others that the document exists and where it is. A person may want to carry it with them in case of emergency, or carry a card, bracelet or other indication that they have made an advance decision and explaining where it is kept.

There is no set format for written advance decisions, because contents will vary depending on a person’s wishes and situation. But it is helpful to include the following information:

■ full details of the person making the advance decision, including date of birth, home address and any distinguishing features (in case healthcare professionals need to identify an unconscious person, for example)

■ the name and address of the person’s GP and whether they have a copy of the document

■ a statement that the document should be used if the person ever lacks capacity to make treatment decisions

■ a clear statement of the decision, the treatment to be refused and the circumstances in which the decision will apply

■ the date the document was written

■ the date when the document should be reviewed (the document must not have a ‘valid until’ date)

■ the person’s signature (or the signature of someone the person has asked to sign on their behalf, and in their presence)

■ the signature of the person witnessing the signature, if there is one (or a statement directing somebody to sign on the person’s behalf).

Whilst it is preferable to have a written advance decision to refuse treatment, it is possible to have oral advance decisions. There is no set format for oral advance decisions. This is because they will vary depending on a person’s wishes and situation. Healthcare professionals will need to consider whether an oral advance decision exists and whether it is valid and applicable.

Where possible, healthcare professionals should record an oral advance decision to refuse treatment in a person’s healthcare record. This will produce a written record that could prevent confusion about the decision in the future.

It is essential that where an advance directive is made, a copy of this is held in the individual’s clinical records and that the individual is encouraged to share copies with family and those health and social care professionals coordinating their care.

An advance directive must be followed where it is concluded that an individual lacks capacity to make a specific decision about their medical treatment and it is known that they have previously made a valid and applicable advance directive (relating to the proposed specific medical treatment). If it is a refusal of life sustaining treatment then it must contain a statement that the advance decision applies even if your life is at risk. Decision makers are advised to consult senior clinicians as required (MCA Draft Code of Practice, 2022).

-

LPAs were introduced by the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and replaced Enduring Powers of Attorney (EPA). No new EPA could be set up after 1st October 2007, but pre-existing ones are still valid.

An LPA is a legal document that allows someone to plan ahead for a possible future loss of mental capacity. It allows the person (called “the donor”) to appoint a trusted person or people (called “attorneys” or “donees”) to make financial and/or personal welfare decisions on their behalf. Using an LPA, the attorney can make decisions that are as valid as those made by the person.

There are two types of LPA;

■ property and affairs – covering finances, money and property

■ personal welfare – covering healthcare, social care and consent to medical treatment. This is often called a ‘health and welfare’ or ‘health and care decisions’

LPA Details:

A Service User can decide to make one type of LPA or both, but both types must be on prescribed documentation and registered with the Office of the Public Guardian before they can be used, or they are not valid.

Once registered, a property and affairs LPA can be used when the donor has capacity, if the donor has specified that in the LPA, and if they have given permission to make the decision. But a personal welfare LPA can only be used if the donor does not have capacity to make the decision.

Only adults aged 18 or over can make an LPA, and they can only make an LPA if they have the mental capacity to do so. This does not mean the donor needs to have the capacity to make all decisions at the time they make the LPA. It means they must have the mental capacity to decide to make and then execute the LPA even if they lack the mental capacity to make some of the decisions the LPA would cover.

Where it is concluded that an individual lacks capacity to make a decision and they have a LPA or deputy then, unless there are safeguarding concerns about the LPA or deputy, the decision maker is the donee of LPA or the Deputy.

All LPA are registered with the Office of the Public Guardian. Any staff completing an MCA where an LPA is in place will need to request to see a copy of the document. Where this is not forthcoming the Office of the Public Guardian can be contacted to verify the existence of the LPA by completing form OPG 100.

See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/search-public-guardian-registers

If you are concerned that donee of the LPA or the Deputy is not acting in the best interests of the individual, then you must raise an urgent safeguarding alert and discuss the matter with your line manager urgently as legal action may be required. The Office of the Public Guardian will also need to be notified and will investigate and have the power to revoke an LPA if the attorney is not acting in the best interests of the donee.

If the person has an advanced decision made prior to the appointment of an attorney the attorney can decide whether to override the advance decision. If the advance decision was made after the appointment of the attorney, it must stand. Not all attorneys will have been given the power to decide on life-sustaining treatment. The lasting power of attorney form must clearly state this authority.

Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) predates the Mental Capacity Act, that came into force in 2007 and is for property and finance only. Any Enduring Power of Attorney that was made before October 2007 can still be used by attorneys to meet the données expectation for when they lost capacity. Some données will have cancelled the EPA and created an LPA but others will have lacked capacity to do this. EPA does not include decisions about Health and Welfare.

Court Appointed Deputies

Whilst Lasting Power of Attorney is given by the person while they still have capacity to choose who they wish to make decisions for them, some people including those with Profound Multiple Learning Disabilities may never regain capacity to make their own decisions. Family members can apply to the Court of Protection to be appointed as deputies. This holds a greater level of accountability and is monitored through the office of the Public Guardian and requires annual fees to be paid.

The Court of Protection has powers to appoint deputies to make decisions for people lacking capacity to make those decisions, and to remove deputies who fail to carry out their duties.

If the court thinks that somebody needs to make future or ongoing decisions for someone whose condition makes it likely they will lack capacity to make some further decisions in the future, it can appoint a deputy to act for and make decisions for that person. A deputy’s authority should be as limited in scope and duration as possible in order to be a less restrictive way forward.

It is for the court to decide who to appoint as a deputy. This decision must be in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity. Different skills may be required depending on whether the deputy’s decisions will be about a person’s welfare (including healthcare), their finances or both. The court will decide whether the proposed deputy has an appropriate level of skill and competence to carry out the necessary tasks.

In many cases, the deputy is a family member or someone who knows the person well. But in some cases, the court may decide to appoint a deputy who is independent of the family (for example, where the person’s affairs or care needs are particularly complicated). This could be, for example, a relevant office holder in the relevant local authority or a professional deputy. The OPG has a panel of professional deputies (mainly solicitors who specialise in this area of law) who may be appointed to deal with property and affairs if the court decides that would be in the person’s best interests, for instance if there is no one else to take on the role (to respect the degree of trust placed in them by the court).

Records detailing accounts of all their dealings and transactions on the person’s behalf must be made and retained.

Anyone acting as a deputy must follow the Act’s statutory principles including:

■ Considering whether the person has capacity to make a particular decision for themselves. If they do, the deputy should allow them to do so unless the person agrees that the deputy should make the decision.

■ Taking all possible steps to try to help a person make the particular decision.

■ Always make decisions in the person’s best interests and have regard to guidance in the Code of Practice that is relevant to the situation.

■ Only make those decisions that they are authorised to make by the order of the court.

■ Fulfil their duties towards the person concerned.

■ Keep, correct accounts of all their dealings and transactions on the person’s behalf and periodically submit these to the Public Guardian as directed, so that the OPG can carry out its statutory function of supervising the deputy.

Before completing a best interest decision on behalf of someone assessed as lacking capacity to make the decision, staff should check whether a deputy has been appointed and if so, should consult with them regarding the decision.

-

The Office of the Public Guardian protects people who may lack capacity to make certain decisions for themselves. They supervise people appointed by the Court of Protection to help manage someone’s affairs where they have lost mental capacity and help people to plan ahead to help them appoint someone they trust to make decisions for them if they lose capacity.

The main areas of work they are involved in are:

■ Registering Powers of Attorney

■ Supervising deputies

■ Maintaining the public register of Attorneys and deputies

■ Safeguarding and investigations where there are allegations that attorneys or deputies are not acting in the best interests of the person they are responsible for. These powers can be removed if the person is found to be abusing their position.

-

The Court of Protection has powers to:

■ Decide whether a person has capacity to make a particular decision for themselves.

■ Make declarations, decisions or orders on financial or welfare matters affecting people who lack capacity to make such decisions.

■ Appoint deputies to make decisions for people lacking capacity to make those decisions.

■ Decide whether an LPA or EPA is valid, and

■ remove deputies or attorneys who fail to carry out their duties.

The Court of Protection is a superior court of record and is able to establish precedent (it can set examples for future cases) and build up expertise in all issues related to lack of capacity. It has the same powers, rights, privileges and authority as the High Court. When reaching any decision, the court must apply all the statutory principles set out in section 1 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

In cases where there is doubt or disagreement between those interested in the person’s welfare which cannot be resolved, the court should be asked to make the decision on their behalf if it is believed that they do not have capacity to make the decision for themselves.

The court will not intervene and rule on cases where the person has capacity to make their own decision even if others consider the decision unwise.

It can make a declaration as to whether a person has capacity to make a particular decision or give consent to a particular action. The court will require evidence of any assessment of the person’s capacity, is likely to want to see relevant written evidence (for example, a diary, letters or other papers), and may wish to hear evidence from professionals, family members and friends. If the court decides the person has capacity to make that decision, they will not take the case further. The person can then make the decision for themselves.

If the court has declared that a person lacks capacity to make a specific decision or decisions, it can make the decision for the person, either by appointing a deputy or making the decision itself on behalf of the person.

When the court is making the decision itself, it is choosing between the options which are available to the person at the time and are in their best interests.

The court will deal with serious decisions affecting health and personal welfare as well as property and affairs. Any decision must be made in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity to make the specific decision. If the decision is in relation to medical treatment, the court is consenting or refusing on behalf of the person. If the court refuses medical treatment on behalf of the person, then it will not be lawful to give it. (MCA, Draft Code of Practice, 2022)

Applications to the Court of Protection can be made on behalf of a person by any interested party including family, health or social care depending on the circumstances of the dispute.

-

The first principle of the Mental Capacity Act is that people must be assumed to have capacity to make a decision or act for themselves unless it is established that they lack it. People with capacity are able to decide for themselves what they want to do and what they don’t want to do. When they do this, they might choose an option that other people don’t think is in their best interests. That is their choice and does not in itself mean that they lack capacity to make those decisions. However, there may be indications of a lack of capacity if the decision is uncharacteristic or exposes the person to risk or danger. Deciding a person’s best interests is therefore only relevant after all practicable steps have been taken without success to support the person to make the decision in question or give consent to an act being done.

Working out what is in someone else’s best interests may be difficult, and the Act requires people to follow certain steps to help them work out whether a particular act or decision is in a person’s best interests. In some cases, there may be disagreement about what someone’s best interests really are. As long as the person who acts or makes the decision has followed the steps to establish whether a person has capacity, and done everything they reasonably can to work out what someone’s best interests are, the law should protect them.

The majority of best interest decisions will involve a choice, either between a person doing something and not doing something (for instance carrying out a procedure), or making a choice on behalf of the individual between two or more options (for instance where they might live). Where the choice is being made on behalf of the individual, that choice can only be between options which are available to them.

A person trying to work out the best interests of a person who lacks capacity to make a particular decision should:

Identify the available options

If a particular option is not available, then no determination can be reached that this would be in the person’s best interests.

Avoid discrimination

Do not make assumptions about someone’s best interests simply on the basis of the person’s age, appearance, condition or behaviour.

Identify all relevant circumstances

Try to identify all the things that the person who lacks capacity would take into account if they were making the decision or acting for themselves.

Assess whether the person might regain capacity

Consider whether the person is likely to regain capacity (e.g. after receiving medical treatment). If so, can the decision wait until then?

Encourage participation

Do whatever is possible to permit and encourage the person to take part, or to improve their ability to take part, in making the decision.

Find out the person’s views

Try to find out the views of the person who lacks capacity, including:

■ the person’s past and present wishes and feelings – these may have been expressed verbally, in writing or through behaviour or habits.

■ any beliefs and values (e.g. religious, cultural, moral or political) that would be likely to influence the decision in question.

■ any other factors the person themselves would be likely to consider if they were making the decision or acting for themselves.

If the decision concerns life -sustaining treatment, it should not be motivated in any way by a desire to bring about the person’s death.

They should not make assumptions about the person’s quality of life.

Consult others

If it is practical and appropriate to do so, consult other people for their views about the person’s best interests and to see if they have any information about the person’s wishes and feelings, beliefs and values. Try to consult:

■ anyone previously named by the person as someone to be consulted on either the decision in question or on similar issues

■ anyone engaged in caring for the person

■ close relatives, friends or others who take an interest in the person’s welfare

■ any attorney appointed under a Lasting Power of Attorney or Enduring Power of Attorney made by the person

■ any deputy appointed by the Court of Protection to make decisions for the person.

For decisions about major medical treatment or where the person should live and where there is no-one who fits into any of the above categories, an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) must be consulted.

Avoid restricting the person’s rights

See if there are other options that may be less restrictive of the person’s rights and explaining the reasoning if the less restrictive option is not pursued. Think about how you will complete the care or treatment if the person is not co-operative.

Weigh up all of these factors to work out what is in the person’s best interests. (MCA Draft Code of Practice, 2022).

Any staff involved in the care of a person who lacks capacity should make sure a record is kept of the process of working out the best interests of that person using a balance sheet approach and setting out:

■ Who was consulted to help work out best interests,

■ All the possible options for consideration

■ The pro and cons of each option

■ How the decision about the person’s best interests was reached

■ What the reasons for reaching the decision were

■ What factors were taken into account

It may be necessary to convene a best interest meeting with all interested parties to formulate a decision

The Capacity Assessment and Best Interests Decision should be recorded on the MCA Assessment form.

-

Anyone who wants out to carry an act in connection with the care or treatment of another will only be protected from criminal and civil liability if they reasonably believe that the person lacks capacity to make the relevant decision and that the action to be taken is in the person’s best interests.

Wherever appropriate, a decision as to what is in the best interests of a person unable to take the relevant decision should be reached informally and collaboratively between those involved in their care or interested in their welfare, whether paid/professional or unpaid. This means that:

■ The fact that someone is seen as the person’s next of kin does not mean that they have any legal right to make any decision on their behalf;

However,

■ A professional does not have a right to make the decision on behalf of the person simply because they occupy a particular position.

In some cases, the person who is going to carry out the act could be thought of as “the decision-maker” because they are having to decide whether they have the necessary reasonable belief to be able to benefit from the protection from liability. For instance:

■ A GP taking a blood sample from a patient who they reasonably believe to lack capacity to consent would be the decision-maker as to whether taking that blood is in their patient’s best interests.

■ The paid care worker who has to decide whether to step in to intervene to prevent a person with dementia from injuring themselves will have to decide there and then whether they reasonably believe that the person lacks capacity and that the step is in their best interests.

If a Lasting Power of Attorney or Enduring Power of Attorney has been made and registered, or a deputy has been appointed under a court order, then the attorney or deputy will be the decision-maker for decisions within the scope of their authority.

In other cases, the person actually carrying out the act will be acting on the direction or under the supervision of another, or subject to a care plan drawn up by someone else. In each case, the person will themselves have to be satisfied that they are acting in the best interests of the individual before carrying out the act, but are likely to being relying upon the views set down in the care plan. In that case, it will be the person who is responsible for the care plan who could be thought of as “the decision-maker.”

It is important that everyone involved in the best interests decision-making process knows and agrees who the decision-maker is, and that, no matter who is making the decision, the most important thing is that the decision-maker tries to work out what would be in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity. The decision-maker should try to identify any of their own unconscious biases to ensure they do not influence the best interests’ decision. (MCA Draft Code of Practice, 2022).

-

An Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) must be instructed via Local Authority, and then consulted, for people lacking capacity who have no-one else to support them, other than paid staff.

An Independent Mental Capacity Advocate MUST be appointed where it is determined that an adult lacks capacity and has nobody to support them (other than paid staff) and a specific decision is being made about:

■ A change of accommodation – a move to a care home for more than 8 weeks or an admission to a hospital bed for 28 days or more

■ Serious medical treatment.

An IMCA must be instructed for people who:

■ Lack capacity to make a specific decision about serious medical treatment or long-term accommodation, and

■ Have no person (other than paid staff) who it would be appropriate to consult in determining the person’s best interests, and

■ Have not previously named someone who could help with a decision, and

■ Have not made a relevant Lasting Power of Attorney or Enduring Power of Attorney

The IMCA’s role is to independently represent and support the person who lacks the relevant capacity. Their views should not be influenced by how the IMCA service is funded.

To carry out their role, IMCAs have a right to see and take copies of relevant health and social care records.

Any information or reports provided by an IMCA must be considered when determining whether a proposed decision is in the person’s best interests.

In London, IMCA referral forms go through Local Authority (Boroughs/Councils), or Local Health Board contacts and their independent advocacy providers.

DDCS contracts that operate in other counties and regions will require local safeguarding contacts to be added in due course.

Contact the Safeguarding Lead for support with making an IMCA referral. Council/Borough - directed IMCA referrals may change providers, so contact Boroughs directly for the most up-to-date information.

IMCA referral details by area

■ For Barking and Dagenham, Kingston upon Thames → Cambridge House

Website: https://ch1889.org/advocacy/

Phone: 020 7358 7007

Email (Barking and Dagenham): chadvocacy@ch1889.org

Email (Kingston upon Thames): imca@ch1889.org

■ For Barnet, Brent, City of London, Enfield, Greenwich, Haringey, Harrow, Hillingdon, Hounslow, Kensington and Chelsea, Lewisham, Tower Hamlets, Waltham Forest → POhWER:

Website: https://www.pohwer.net/make-a-referral

Phone: 0300 456 2370

Email: nhscomplaints@pohwer.net

■ For Bexley, Bromley, Croydon, Sutton → Advocacy for All

Website: https://www.advocacyforall.org.uk/make-a-referral/

Email:referrals@advocacyforall.org.uk

■ For Camden, Hackney, Islington, Richmond upon Thames, Wandsworth → Rethink Advocacy

Website: https://www.rethink.org/help-in-your-area/services/advocacy/rethink-advocacy-london-hub/

Phone: 0300 790 0559

Email: advocacyreferralhub@rethink.org

■ For Ealing → The Advocacy Project

Website: https://www.advocacyproject.org.uk/home/advocacy/advocacy-referrals/

Email: info@advocacyproject.org.uk

■ For Hammersmith and Fulham → Libra Partnership

Website: https://referral.librapartnership.co.uk/

Phone: 0333 305 1329

■ For Havering → Mind

Website: https://www.haveringmind.org.uk/services/havering-statutory-independent-advocacy-service/

Phone: 01708 457040

Email: advocacy@haveringmind.org.uk

■ For Lambeth, Merton, Newham, Redbridge → VoiceAbility

Website: https://www.voiceability.org/make-a-referral

Phone: +44(0)300 303 1660

Email: helpline@voiceability.org

■ For Southwark → The Advocacy People

Website: https://www.theadvocacypeople.org.uk/services/advocacy-for-people-who-lack-capacity

Phone: 0330 440 9000

-

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 states that everyone aged 16 and over is presumed to have capacity. The Children Act 1989 notes that a young person does not legally become an adult until their 18th birthday and Section 8 of the Family Law Reform Act 1969 provides that young people age 16 and 17 have the right to consent to treatment and that such treatment can be given without the need to obtain the consent of a person with parental responsibility.

Where a young person aged 16 and over has capacity and does not consent to a decision, their wishes and views must be upheld. Professionals are advised against relying on the consent of a person with parental responsibility and are advised to seek legal advice if required.

Where a young person aged 16 and over lacks capacity to make a specific decision, the decision should be taken within the framework of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 with three exceptions:

■ Only people aged 18 and over can make a Lasting Power of Attorney.

■ Only people aged 18 and over can make an advance decision to refuse medical treatment.

■ The Court of Protection may only make a statutory will for a person aged 18 and over.

The same principles and approach that apply to adults apply to young people aged over 16 to determine their best interests regarding care or treatment when they lack capacity to make a specific decision. This means considering what would be in their best interests and consulting with family and other professionals to ascertain what is right for the young person when the decision needs to be made.

Professionals may consider it more appropriate, due to the circumstances of the case, to rely upon the consent of a person with parental responsibility regarding the young person’s care and treatment. Professionals should be clear and explicit as to which framework is appropriate and why.

Clinicians are reminded that young people under the age of 16 may still have capacity or be Gillick-competent to make a decision. For a young person under the age of 16, the professional has a duty to evidence that the young person has capacity or is Gillick-competent, whilst for the young person aged 16 and over the law presumes the young person has capacity to make all decisions.

Either the Family Court or the Court of Protection can hear cases involving young people aged 16 or 17 who lack capacity.

As part of transitioning from child to adult services, staff working with families where the young person is unlikely to regain capacity, such as those with a Profound Multiple Learning Disability (PMLD), should empower parents with the knowledge and awareness on the process of applying to the Court of Protection for deputyship to gain legal powers to make decisions around care and treatment or finance for their young person. Applications to the Court of Protection will be considered once the young person reaches the age of 16, although families should be encouraged to consider this once the young person reaches the age of 14, as part of transitioning to adult services.

See Mencap MCA Resource pack: https://www.mencap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2016-06/mental%20capacity%20act%20resource%20pack_1.pdf (mencap.org.uk)

-

If a dispute arises, please contact the DDCS Safeguarding Lead immediately.

There are likely to be occasions when someone may wish to challenge the results of an assessment of capacity. The first step is to raise the matter with the person who carried out the assessment. It is the decision-maker who has the final determination regarding the outcome of the assessment. If the challenge comes from the individual who is said to lack capacity, they might need support from family, friends or an advocate.

Professionals should consider the concerns of family or friends if they dispute the outcome of an assessment and, where necessary, they can request a second opinion or (where a dispute is anticipated prior to the assessment occurring), consider the use of two professionals to jointly assess an individual’s capacity to make a specific decision.

Where, having involved a second professional, there is disagreement between them about the outcome, then it must be presumed that the individual does have capacity. Specialist assessments of mental capacity can be commissioned from independent assessors in exceptional circumstances. Also, the ultimate arbiter in resolving disputes in relation to assessments of mental capacity or best interests is the Court of Protection. Legal advice or advice from safeguarding should be sought in these situations.

-

Section 44 of the Act introduces a new criminal offence of ill treatment and wilful neglect of a person who lacks capacity. It applies to:

■ Anyone caring for a person who lacks capacity

■ An attorney appointed under Lasting Power of Attorney

■ A deputy appointed for the person by the Court

Ill treatment: the person must either have deliberately ill-treated the person or be reckless in the way they were treating the person such as to be likely to cause harm or damage to the victim’s health.

Wilful neglect: the meaning varies depending on the circumstances, but usually means a failure to carry out an act the person knew they had a duty to do.

-

The Mental Health Act 1983, (MHA) provides the legal framework for the assessment, detention and treatment of people when they have a serious mental disorder that puts them or other people at risk. The MHA includes provisions for civil patients and those who go to hospital through decisions made in the criminal justice system.

Its provisions include powers for when people with mental disorders can be detained in hospital for assessment or treatment; and when people who are detained can be given treatment for their mental disorder without their consent.

Generally, the MHA does not distinguish between people who have the capacity to make decisions and people who do not. Many people subject to the MHA have the capacity to make specific decisions for themselves. But there are cases where decision makers will need to decide whether to use the MHA or MCA, or both, to meet the needs of people with a mental health condition who lack capacity to make decisions about their own treatment. (MCA Draft Code of Practice, 2022)

The MCA applies to people subject to the MHA in the same way as it applies to anyone else, with four exceptions:

If someone is detained under the MHA, decision-makers cannot normally rely on the MCA to give treatment for mental disorder or make decisions about that treatment on that person’s behalf

If somebody can be treated for their mental disorder without their consent because they are detained under the MHA, healthcare staff can treat them even if it goes against an advance decision to refuse that treatment

If a person is subject to guardianship, the guardian has the exclusive right to take certain decisions, including where the person is to live, and

Independent Mental Capacity Advocates do not have to be involved in decisions about serious medical treatment or accommodation, if those decisions are made under the MHA. (MCA Draft Code of Practice, 2022)

-

United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006, adopted by UK in 2009

HM Gov 2021

Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice

http://www.publicguardian.gov.uk/docs/Mental Capacity Act-code-practice-0509.pdf

Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019

Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019 (legislation.gov.uk)

Cheshire West and Chester Council v P [2014] UKSC19

https://www.supremecourt.uk/decided-cases/docs/UKSC_2012_0068_Judgment.pdf

1948 European Convention on Human Rights

https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/convention_eng.pdf

NSPCC Guide on Gillick competencies and Fraser guidelines https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/child-protection-system/gillick-competence-fraser-guidelines

Appendix A Outline of the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards – HM Gov 2021

The amendment to the Mental Capacity Act 2005 introduces a new process for authorising Deprivations of Liberty safeguards for people who lack capacity to make a particular decision.

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards will be replaced by Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS) and it is proposed that any existing DoLS already in place will run until they expire and will then be reviewed under Liberty Protection Safeguards.

The key changes are:

■ Three assessments: MCA, Medical assessment, and Necessary & Proportionate assessment.

■ Greater involvement for families with an explicit duty to consult with those caring for the person and those interested in their welfare. Family members can act as an appropriate person to represent and support the person through the process.

■ Targeted approach where cases can be referred to an Approved Mental Capacity Professionals (AMCP) for consideration, if it is reasonable to believe that a person would not wish to reside or receive care or treatment at the specified place, or the arrangements provide for the person to receive care or treatment apply mainly in an independent hospital.

■ LPS is being extended to include 16-17-year-olds.

■ LPS will also apply in Domestic settings including the person’s own and family home, shared living and Supported living.

■ Supervisory Body will be replaced with Responsible Body. These will be:

NHS foundation trusts for hospital inpatients,

ICSs for CHC funded domiciliary patients

Local Authorities for all others.

■ Introduces an element of ‘portability’ from one setting to another.

(DHSC, 2021)

Table 1: Examples of who should assess capacity

Acknowledgements

Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice Code of Practice HM Gov 2013

Provide Safeguarding Policy suite Transforming Lives with Innovative Health and Social Care | Provide Community

Social Care Institute for Excellence https://www.scie.org.uk/mca/dols/at-a-glance/

Making decisions: the Independent Mental Capacity Advocate service (web version) HM Gov https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-mental-capacity-advocates/making-decisions-the-independent-mental-capacity-advocate-service-web-version

Policy updates

The Director and Programme Associates are responsible for updating this policy. This policy will be adapted to reflect changes in national legislation and statutory guidance and delivery in accordance with local safeguarding and other relevant partnership arrangements.

This statement is approved by the Director, Dan Devitt.

Questions, comments and requests regarding this policy are welcomed and should be addressed to info@ddconsultancyservices.com.

Version 1.0, adopted 18th November 2025